Madam C.J. Walker was born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867, near Delta, Louisiana. After suffering from a scalp ailment that resulted in her own hair loss, she invented a line of African-American hair care products in 1905. She promoted her products by traveling around the country giving lecture-demonstrations and eventually established Madame C.J. Walker Laboratories to manufacture cosmetics and train sales beauticians. Her savvy business acumen led her to be one of the first American women to become a self-made millionaire. She was also known for her philanthropic endeavors including donating the largest amount of money by an African-American toward the construction of an Indianapolis YMCA in 1913.

Around the time of the 1904 World's Fair, she became a commission agent selling products for Annie Turnbo Malone, an African American hair care entrepreneur. While working with Annie Malone, she adapted her knowledge of hair and hair products. She moved to Denver to work on her hair care products, and married Charles Joseph Walker, a newspaper advertising salesman. She emerged with the name Madam C. J. Walker, an independent hairdresser and retailer of cosmetic creams. After their marriage Charles Walker provided advice on advertising and promotion, while Madam C. J. Walker trained women to become "beauty culturists" and to learn the art of selling. In 1906, Madam Walker put her daughter A'Lelia (née McWilliams) in charge of the mail order operation while she and her husband traveled throughout the southern and eastern United States to expand the business.

While her daughter Lelia (later known as A'Lelia Walker) ran the mail order business from Denver, Madam Walker and her husband traveled throughout the southern and eastern states. They settled in Pittsburgh in 1908 and opened Lelia College to train "hair culturists." In 1910 Walker moved to Indianapolis where she established her headquarters and built a factory, hair salon, and beauty school to train her sales agents. She later added a laboratory to help with research.Sarah, now known as Madam C. J. Walker, was becoming very successful. Her business market expanded beyond the United States to Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, Panama, and Costa Rica.

Inspired by the model of the National Association of Colored Women, she began to organize her sales agents into local and state clubs. In 1917 she convened her first annual conference of the Madam Walker Beauty Culturists in Philadelphia. During the convention she gave prizes not only to the women who had sold the most products and brought in the most new sales agents, but also to those who had contributed the most to charity in their communities. She stressed the importance of philanthropy and political engagement.This had a huge impact on expanding her business. She also started her own mail order business to keep up with the booming business, placing her daughter A’Lelia Walker in charge of it.

She began to teach and train other black women in women's independence, budgeting, and grooming in order to help them build their own businesses. She also gave lectures on political, economic and social issues at conventions sponsored by powerful black institutions. In 1917 she started the Walker Hair Culturists Union of America convention, which ended up being the first national meeting of American women brought together to discuss business and commerce. She became involved in political matters, joining the executive committee of the Silent Protest Parade. It was a public demonstration of more than 8,000 African Americans to protest a riot that killed 39 African Americans.

In 1917, she commissioned Vertner Tandy, the first licensed black architect in New York State and a founding member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, to design a house for her in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, Villa Lewaro.The house cost $250,000 to build.She moved into Villa Lewaro in May 1918 and hosted an opening event to honor Emmett Scott, then the Assistant Secretary for Negro Affairs of the United States War Department.

Just before her death she pledged $5,000, the equivalent of about $65,000 in 2012, to the NAACP's anti-lynching fund. Madam C. J. Walker died at Villa Lewaro on Sunday, May 25, 1919,from complications of hypertension. She was 51. In her will she directed two-thirds of future net profits of her estate to charity; she bequeathed nearly $100,000 to orphanages, institutions, and individuals.At her death she was considered to be the wealthiest African-American woman in America. According to Walker's New York Times obituary, "she said herself two years ago [in 1917] that she was not yet a millionaire, but hoped to be some time."Her daughter, A'Lelia Walker, became the president of the Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company.

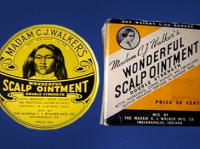

The Walker System

Madam Walker's System included a shampoo, a pomade stated to help hair grow, strenuous brushing and applying iron combs to hair. This method claimed to transform lusterless and brittle hair into soft luxurious hair. The manufacturing company employed women who, dressed in a characteristic uniform of white shirts and black skirts, and carrying black satchels, made house calls widely around the United States and in the Caribbean. The pomade and other products were packaged in tin containers carrying a picture of Madame Walker, which, accompanied by heavy advertising, made Madame Walker well known in the US and more widely in the 1920s. Similar products came to be produced in Europe and by other companies in the United States, including those set up by Mrs. Annie M. Turnbo Malone ("Poro System") and Madame Sarah Spencer Washington ("Apex System".)