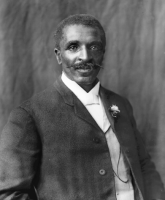

George Washington Carver was an agricultural chemist and botanist whose colorful life story and eccentric personality transformed him into a popular American folk hero to people of all races. Born into slavery, he spent his first 30 years wandering through three states and working at odd jobs to obtain a basic education. His lifelong effort thereafter to better the lives of poor Southern black farmers by finding commercial uses for the region’s agricultural products and natural resources—in particular the peanut, sweet potato, cowpea, soybean, and native clays from the soil—brought him international recognition as a humanitarian and chemical wizard. An accomplished artist and pianist as well, Carver was among the most famous black men in the United States during the early twentieth century.

Early Life

Carver was born into slavery in Diamond Grove, Newton County, near Crystal Place, now known as Diamond, Missouri, possibly in 1864 or 1865, though the exact date is not known.His master, Moses Carver, was a German American immigrant who had purchased George's parents, Mary and Giles, from William P. McGinnis on October 9, 1855, for $700. Carver had 10 sisters and a brother, all of whom died prematurely.

When George was only a week old, he, a sister, and his mother were kidnapped by night raiders from Arkansas.George's brother, James, was rushed to safety from the kidnappers.The kidnappers sold the slaves in Kentucky. Moses Carver hired John Bentley to find them, but he located only the infant George. Moses negotiated with the raiders to gain the boy's return,and rewarded Bentley.

After slavery was abolished, Moses Carver and his wife Susan raised George and his older brother James as their own children.They encouraged George to continue his intellectual pursuits, and "Aunt Susan" taught him the basics of reading and writing.

Black people were not allowed at the public school in Diamond Grove. Learning there was a school for black children 10 miles (16 km) south in Neosho, George decided to go there. When he reached the town, he found the school closed for the night. He slept in a nearby barn. By his own account, the next morning he met a kind woman, Mariah Watkins, from whom he wished to rent a room. When he identified himself as "Carver's George," as he had done his whole life, she replied that from now on his name was "George Carver". George liked Mariah Watkins, and her words, "You must learn all you can, then go back out into the world and give your learning back to the people", made a great impression on him.

At the age of thirteen, due to his desire to attend the academy there, he relocated to the home of another foster family in Fort Scott, Kansas. After witnessing a black man killed by a group of whites, Carver left the city. He attended a series of schools before earning his diploma at Minneapolis High School in Minneapolis, Kansas.

Carver’s Legacy

Carver left his life savings of $60,000 to found the George Washington Carver Foundation—to provide opportunities for advanced study by blacks in botany, chemistry, and agronomy— and the Carver Museum, to preserve his scientific work and paintings at Tuskegee. The site of Moses Carver’s farm is now the George Washington Carver National Monument. A U.S. postage stamp was issued in the agricultural pioneer’s honor, and Congress has designated January 5, the day of his death, to pay tribute to him each year.

At his death from complications of anemia in 1943, Carver remained the most famous African-American of his era, world renowned as a scientific wizard. However, none of his hundreds of formulas for peanut, sweet potato, and other by-products became successful commercial products. Nor was he solely instrumental in diversifying Southern agriculture from cotton to peanuts and other crops. The great boom in Southern peanut production occurred prior to World War I and Carver’s bulletins promoting the crop.

Carver’s true importance in history lay elsewhere. For nearly 50 years he remained in the South, working to improve the lives of the region’s many poor farmers, black and white. Through his talents as an interpreter and promoter, he put the agricultural discoveries and technical writings of leading scientists in everyday language that ill-educated farmers could understand and use. And in an age of strict racial segregation, his importance as a role model and national symbol of black ability, education, and achievement cannot be undervalued.