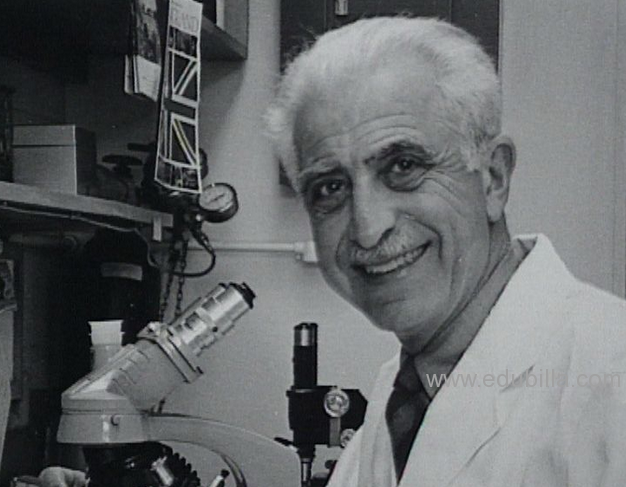

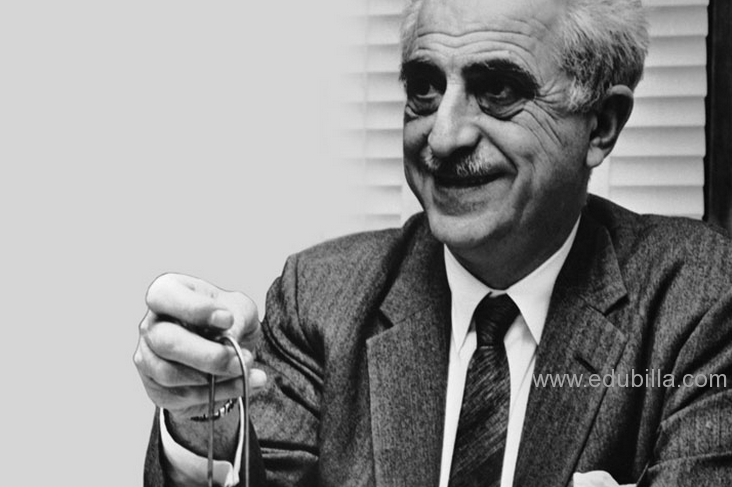

A pioneer in early hormonal and reproductive research, Gregory Pincus and his team of scientists are credited with formulating the first oral contraceptive for birth control.

Coming from a family of agriculturists, Gregory Pincus, born in New Jersey on April 9, 1903, took his environmental learning to the next step, experimenting with reproductive cycles of animals and in vitro fertilization, which led to the discovery of an oral contraceptive. Known as the Pill, it gave women more control over their own bodies, helped with population control, and accelerated the sexual revolution.

Gregory Goodwin Pincus was a first-generation American born to Jewish immigrants Elizabeth Lipman and Joseph Pincus on April 9, 1903, in Woodbine, New Jersey. He was surrounded by agriculturalists. His father, who graduated from Storrs Agricultural College in Connecticut, taught the discipline and was founding editor of a farm journal. His mother's brother was dean of the New Jersey State College of Agriculture at Rutgers University, as well as founder of Soil Science magazine.

An honor student, Pincus pursued genetics, but he also had literary interests. Earning both his master's and doctorate degrees by the time he was 24, Pincus was granted a fellowship from the National Research Council, which allowed him to travel to Cambridge, England, aligning himself with pioneers in reproductive biology and genetics.

Scientific Career

Though he was hired as a teaching professor at Harvard University, pure research and lab work was always a stronger draw for Gregory Pincus. His focus was on inherited traits, but he eventually moved over to reproduction. Early experiments in transferring eggs from one animal to another prefigured the surrogate mother model. Work in this area did not just yield reproductive insights, though; Pincus also examined whether diabetes was inherited, the connection between stress and hormones, and what role the endocrine system playsin mental disorders.

Pincus's breakthrough research on the breeding of rabbits without males via artificial insemination in 1939 caused wide excitement, even outside scientific circles. However, other researchers were not able reproduce the results. There's also speculation that these experiments with rabbits had a negative effect on Pincus attaining tenure at Harvard.

Pincus went on to join his grad school friend, Hudson Hoagland, at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, to teach experimental zoology. They combined forces to research connections between stress and hormones for the U.S. armed forces. They also worked together to found the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology in 1944.

By the early 1950s, Pincus and biologist Dr. Min Chueh Chang were working with progesterone to inhibit ovulation, experimenting with synthetic substances from pharmaceutical companies Searle and Syntex. Fertility specialist Dr. John Rock joined the team and they began human trials in the late 1950s, although there was pushback in Massachusetts from the Catholic church. Margaret Sanger, who founded Planned Parenthood, was a champion of Pincus's work. Finally, in 1960, Enovid became the first oral contraceptive approved by the FDA for marketing in the United States.

Death and Legacy

Dr. Pincus was widely lauded for his work, amassing various awards and recognition, including the Albert D. Lasker Award in Planned Parenthood and the Cameron Prize in Practical Therapeutics from the University of Edinburgh, but the prized feather in his cap was election to the National Academy of Sciences in 1965.

Two years later, however, Dr. Gregory Pincus was felled by a debilitating bone-marrow disorder exacerbated by exposure to lab chemicals. He died at 64 years old, on August 22, 1967, in Boston, Massachusetts. He was survived by his wife, Elizabeth Notkin, whom he had married in 1924, and their three children.

He has received a number of awards. Some of these awards include the Oliver Bird Prize in 1960, the Julius A. Koch Award in 1962, and the American Medical Association's Scientific Achievement Award in 1967.Pincus was acknowledged for his creation of the Laurentian Hormone Conference, which was a conference of endocrinologists. He was the chairman of the conference. The purpose of the conference was to discuss the hormones of the endocrine system. The conference was attended by endocrinologists from all over.