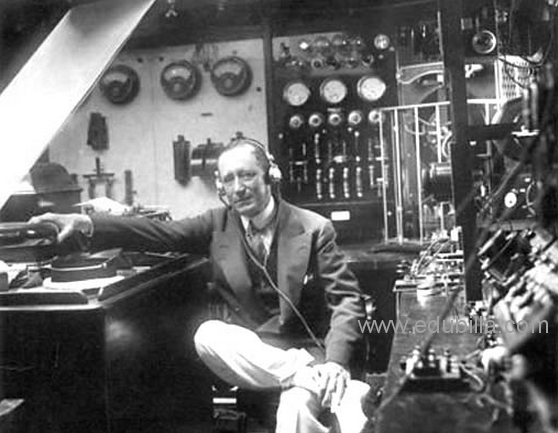

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden was a Canadian inventor who performed pioneering experiments in radio, including the use of continuous waves and the early—and possibly the first—radio transmissions of voice and music. In his later career he received hundreds of patents for devices in fields such as high-powered transmitting, sonar, and television.

Early Life

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden was born October 6, 1866, in East-Bolton, Quebec, the eldest of the Reverend Elisha Joseph Fessenden and Clementina Trenholme. Elisha Fessenden was a minister of the Church of England in Canada, and through the years the family moved to a number of postings within the Province of Ontario.

While growing up, Reginald was an accomplished student. In 1877, at the age of eleven, he attended Trinity College School in Port Hope, Ontario for two years. At the age of fourteen, Bishop's College School in Lennoxville, Quebec granted Fessenden a mathematics mastership. At this time, Bishop's College School was a feeder school of Bishop's University and shared the same campus and buildings. In June 1878, the school had an enrollment of only 43 boys. Thus, while Fessenden was only a teenager, he was teaching mathematics to the young children at the school while simultaneously studying with the older students at Bishop's University. Total enrollment at the university for the school year 1883-84 was twenty-five students. At the age of eighteen, Fessenden left Bishop's without having been awarded a degree, even though he had "done substantially all the work necessary." (This lack of a degree may have hurt Fessenden's employment opportunities; when McGill University established an electrical engineering department, Fessenden was turned down on an application to be the chairman, in favor of an American.)

The next two years he worked as the principal, and sole teacher, at the Whitney Institute in Bermuda. While there, he became engaged to Helen Trott of Bermuda. They married in September 1890 and later had a son-Reginald Kennelly Fessenden.

In the late 1890s, reports began to appear about the success Guglielmo Marconi was having in developing a practical radio transmitting and receiving system. Fessenden began limited radio experimentation, and soon came to the conclusion that he could develop a far more efficient system than the spark-gap transmitter and coherer-receiver combination which had been championed by Oliver Lodge and Marconi.

First Audio Radio Transmission

In 1900 Fessenden left the University of Pittsburgh to work for the United States Weather Bureau, with the objective of proving the practicality of using a network of coastal radio stations to transmit weather information, thus avoiding the need to use the existing telegraph lines. The contract gave the Weather Bureau access to any devices Fessenden invented, but he would retain ownership of his inventions. The contract promised Fessenden $3,000 per year for his work. They also promised to give him work space, assistance, and housing.

Fessenden quickly made major advances, especially in receiver design, as he worked to develop audio reception of signals. His initial success came from a barretter detector, which was followed by the electrolytic detector that consisted of a fine wire dipped in nitric acid, and for the next few years this later device would set the standard for sensitivity in radio reception. As his work progressed, Fessenden also evolved the heterodyne principle, which combined two signals to produce a third audible tone. However, heterodyne reception was not fully practical for a decade after it was invented, since it required a means for producing a stable local signal, which awaited the development of the oscillating vacuum-tube.

The initial work took place at Rock Point, Maryland, located about 80 kilometers (50 mi) downstream from Washington, DC. While there, Fessenden, experimenting with a high-frequency spark transmitter, successfully transmitted speech on December 23, 1900 over a distance of about 1.6 kilometers (one mile), which appears to have been the first audio radio transmission. At this time the sound quality was too distorted to be commercially practical, but as a test this did show that with further technical refinements it would become possible to transmit audio using radio signals.

As the experimentation expanded, additional stations were built along the Atlantic Coast in both North Carolina and Virginia. However, in the midst of promising advances, Fessenden became embroiled in disputes with his sponsor. In particular, he charged that Bureau Chief Willis Moore had attempted to gain a half-share of the patents. Fessenden refused to sign over the rights, and his work for the Weather Bureau ended in August, 1902. This incident recalled F. O. J. Smith, a member of the House of Representatives from Maine, who had managed to gain a one-quarter interest in the Morse telegraph.

Alternator-transmitter and the first audio radio broadcast

The development of a rotary-spark transmitter was something of a stop-gap measure, to be used until a superior approach could be perfected. Fessenden felt that, ultimately, a continuous-wave transmitter — one that produced a pure sine wave signal on a single frequency — would be far more efficient, particularly because it could be used for quality audio transmissions. His design idea was to take a basic electrical alternator, which normally operated at speeds that produced alternating current of at most a few hundred hertz, and greatly speed it up in order to create electrical currents at tens of kilohertz. Thus, the high-speed alternator would produce a steady radio signal when connected to an aerial. Then, by adding a simple carbon microphone in the transmission line, the strength of the signal could be varied in order to add sounds to the transmission. In other words, amplitude modulation would be used to impress audio on the radio frequency carrier wave. However, it would take many years of expensive development before even a prototype alternator-transmitter would be ready and a few more years beyond that for high-power versions to become available.

Fessenden contracted with General Electric to help design and produce a series of high-frequency alternator-transmitters. In 1903, Charles Proteus Steinmetz of GE delivered a 10 kHz version which proved of limited use and could not be directly used as a radio transmitter. Fessenden's request for a faster, more powerful unit was assigned to Ernst F. W. Alexanderson, and in August 1906 he delivered an improved model which operated at a transmitting frequency of approximately 50 kHz, although with far less power than Fessenden's rotary-spark transmitters.

The alternator-transmitter achieved the goal of transmitting quality audio signals, but the lack of any way to amplify the signals meant they were somewhat weak. On December 21, 1906, Fessenden made an extensive demonstration of the new alternator-transmitter at Brant Rock, showing its utility for point-to-point wireless telephony, including interconnecting his stations to the wire telephone network. A detailed review of this demonstration appeared in The American Telephone Journal.

A few days later, two additional demonstrations took place, which may have been the first audio radio broadcasts of entertainment and music ever made to a general audience. (Beginning in 1904, the U.S. Navy had broadcast daily time signals and weather reports, but these employed spark transmitters, transmitting in Morse code). On the evening of December 24, 1906 (Christmas Eve), Fessenden used the alternator-transmitter to send out a short program from Brant Rock. It included a phonograph record of Ombra mai fu (Largo) by George Frideric Handel, followed by Fessenden himself playing on the violin Adolphe Adam's carol O Holy Night, singing Gounod's Adore and be Still, and finishing with reading a passage from the Bible: 'Glory to God in the highest and on earth peace to men of good will'.He petitioned his listeners to write in about the quality of the broadcast as well as their location when they heard it. Surprisingly, his broadcast was heard several hundred miles away; however, accompanying the broadcast was a disturbing noise. This noise was due to irregularities in the spark gap transmitter he used.

On December 31, New Year's Eve, a second short program was broadcast. The main audience for both these transmissions was an unknown number of shipboard radio operators along the East Coast of the United States. Fessenden claimed that the Christmas Eve broadcast had been heard "as far down" as Norfolk, Virginia, while the New Year Eve's broadcast had reached places in the Caribbean. Although now seen as a landmark, these two broadcasts were barely noticed at the time and soon forgotten; the only first-hand account appears to be a letter Fessenden wrote on January 29, 1932 to his former associate, Samuel M. Kinter.There are no known accounts in any ships' radio logs, nor any contemporary literature, of the reported holiday demonstrations.

(Broadcasting historian James E. O'Neal, in a series of articles on the Radio World website,suggests that Fessenden, writing a quarter-century after the fact, may have confused the dates; O'Neal suggests Fessenden was remembering instead a series of tests he'd conducted in 1909.)

There is solid historical evidence, however, that Fessenden's demonstrations of "wireless telephony" were well known at the time. Documentation of Fessenden's demonstration of radio-transmitted voice is provided by a New York Times article, dated Sunday, September 1, 1907, titled: "Telephoning at Sea", which noted "The hertzian waves will penetrate opaque substances, and the amplitude and intensity of the waves may be so varied as to reproduce faithfully the vibrations of the human voice." The same article further states that: "recently, the Fessenden wireless system demonstrated the practicability of transmitting spoken words from a tall mast at Brant Rock to Plymouth, twelve miles away."Intense competition among developers of wireless technology, and the expectation of possible government contracts may have limited the scope of public promotion of the apparatus features and capabilities.

Fessenden's broadcast foreshadowed of the future of radio. (Although primarily designed for transmissions spanning a few kilometers, on a couple of occasions the test Brant Rock audio transmissions were apparently overheard by NESCO employee James C. Armor across the Atlantic at the Machrihanish site).

Later years

Although Fessenden ceased radio activities after his dismissal from NESCO in 1911, he continued to work in other fields. As early as 1904 he had helped engineer the Niagara Falls power plant for the newly formed Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario. However, his most extensive work was in developing a type of sonar system, the so-called Fessenden oscillator, for submarines to signal each other, as well as a method for locating icebergs, to help avoid another disaster like the one that sank Titanic. At the outbreak of World War I, Fessenden volunteered his services to the Canadian government and was sent to London, England where he developed a device to detect enemy artillery and another to locate enemy submarines.

An inveterate tinkerer, Fessenden eventually became the holder of more than 500 patents. He could often be found in a river or lake, floating on his back, a cigar sticking out of his mouth and a hat pulled down over his eyes. At home he liked to lie on the carpet, a cat on his chest. In this state of relaxation, Fessenden could imagine, invent and think his way to new ideas, including a version of microfilm, that helped him to keep a compact record of his inventions, projects and patents. He patented the basic ideas leading to reflection seismology, a technique important for its use in exploring for petroleum. In 1915 he invented the fathometer, a sonar device used to determine the depth of water for a submerged object by means of sound waves, for which he won Scientific American's Gold Medal in 1929.Fessenden also received patents for tracer bullets, paging, television apparatus, turbo electric drive for ships, and more.

After settling his lawsuit with RCA, Fessenden purchased a small estate called "Wistowe" in Bermuda. He died there in 1932 and was interred in the cemetery of St. Mark's Church on the island. An editorial in the New York Herald Tribune said:

It sometimes happens, even in science, that one man can be right against the world. Professor Fessenden was that man. He fought bitterly and alone to prove his theories. It was he who insisted, against the stormy protests of every recognized authority, that what we now call radio was worked by continuous waves sent through the ether by the transmitting station as light waves are sent out by a flame. Marconi and others insisted that what was happening was a whiplash effect. The progress of radio was retarded a decade by this error. The whiplash theory passed gradually from the minds of men and was replaced by the continuous wave, with all too little credit to the man who had been right.

IEEE Medal of Honor