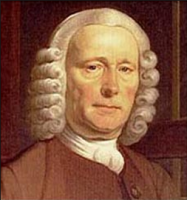

John Harrison was a self-educated English carpenter and clockmaker. He invented the marine chronometer, a long-sought after device for solving the problem of establishing the East-West position or longitude of a ship at sea, thus revolutionising and extending the possibility of safe long-distance sea travel in the Age of Sail. The problem was considered so intractable, and following the Scilly naval disaster of 1707 so important, that the British Parliament offered the Longitude prize of £20,000 (£2.75 million). Harrison came 39th in the BBC's 2002 public poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.

Early life

John Harrison was born in Foulby, near Wakefield in the West Riding of Yorkshire, the first of five children in his family. His father worked as a carpenter at the nearby Nostell Priory estate. A house on the site of what may have been the family home bears a blue plaque.

In around 1700, the Harrison family moved to the Lincolnshire village of Barrow upon Humber. Following his father's trade as a carpenter, Harrison built and repaired clocks in his spare time. Legend has it that at the age of six, while in bed with smallpox, he was given a watch to amuse himself and he spent hours listening to it and studying its moving parts.

He also had a fascination for music, eventually becoming choirmaster for Barrow parish church.

Career

Harrison built his first longcase clock in 1713, at the age of 20. The mechanism was made entirely of wood, which was a natural choice of material for a joiner. Three of Harrison's early wooden clocks have survived: the first (1713) is at the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers' collection in the Guildhall; the second (1715) is in the Science Museum; and the third (1717) is at Nostell Priory in Yorkshire, the face bearing the inscription "John Harrison Barrow". The Nostell example, in the billiards room of this stately home, has a Victorian outer case, which has been thoughtfully provided with small glass windows on each side of the movement so that the wooden workings may be inspected.

In the early 1720s, Harrison was commissioned to make a new turret clock at Brocklesby Park, North Lincolnshire. The clock still works and like his previous clocks has a wooden movement of oak and lignum vitae. Unlike his early clocks, it incorporates some original features to improve timekeeping, for example the grasshopper escapement. Between 1725 and 1728, John and his brother James, also a skilled joiner, made at least three precision longcase clocks, again with the movements and longcase made of oak and lignum vitae. The grid-iron pendulum was developed during this period. These precision clocks are thought by some to have been the most accurate clocks in the world at the time. They are the direct link to the Harrison's sea clocks. No. 1, now in a private collection, belonged to the Time Museum, USA, until the museum closed in 2000 and its collection was dispersed at auction in 2004. No. 2 is in the Leeds City Museum. It forms the core of a permanent display dedicated to John Harrison's achievements, "John Harrison: The Clockmaker Who Changed the World" and had its official opening on 23 January 2014, the first longitude related event marking the tercentenary of the Longitude Act. No. 3 is in the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers' collection.

Harrison was a man of many skills and he used these to systematically improve the performance of the pendulum clock. He invented the gridiron pendulum, consisting of alternating brass and iron rods assembled so that the different expansions and contractions cancel each other out. Another example of his inventive genius was the grasshopper escapement – a control device for the step-by-step release of a clock's driving power. Developed from the anchor escapement, it was almost frictionless, requiring no lubrication because the pallets were made from lignum vitae. This was an important advantage at a time when lubricants and their degradation were little understood.

In his earlier work on the sea clocks, Harrison was continually assisted both financially and in many other ways by George Graham, the watchmaker and instrument maker. Harrison was introduced to Graham by the Astronomer Royal Edmond Halley, who championed Harrison and his work. This support was important to Harrison, as he is supposed to have found it difficult to communicate his ideas in a coherent manner.

The longitude watches

After steadfastly pursuing various methods during thirty years of experimentation, Harrison moved to London in late 1758 where to his surprise he found that some of the watches made by Graham's successor Thomas Mudge kept time just as accurately as his huge sea clocks. It is possible that Mudge was able to do this after the early 1740s thanks to the availability of the new "Huntsman" or "Crucible" steel produced by Benjamin Huntsman sometime in the early 1740s which enabled harder pinions but more importantly, a tougher and more highly polished cylinder escapement to be produced.Harrison then realized that a mere watch after all could be made accurate enough for the task and was a far more practical proposition for use as a marine timekeeper. He proceeded to redesign the concept of the watch as a timekeeping device, basing his design on sound scientific principles.

Memorials

Harrison died on his eighty-third birthday and was buried in the graveyard of St John's Church, Hampstead, in north London, along with his second wife Elizabeth and later their son William. His tomb was restored in 1879 by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, even though Harrison had never been a member of the Company.

Harrison's last home was in Red Lion Square in London, now a short walk from the Holborn Underground station. There is a plaque dedicated to Harrison on the wall of Summit House in the south side of the square. A memorial tablet to Harrison was unveiled in Westminster Abbey on 24 March 2006, finally recognising him as a worthy companion to his friend George Graham and Thomas Tompion, 'The Father of English Watchmaking', who are both buried in the Abbey. The memorial shows a meridian line (line of constant longitude) in two metals to highlight Harrison's most widespread invention, the bimetallic strip thermometer. The strip is engraved with its own longitude of 0 degrees, 7 minutes and 35 seconds West.

The Corpus Clock in Cambridge, unveiled in 2008, is an homage by the designer to Harrison's work but is of an electromechanical design. In appearance it features Harrison's grasshopper escapement, the 'pallet frame' being sculpted to resemble an actual grasshopper. This is the clock's defining feature.

The Notable awards that was received by John Harrison is Copley Medal (1749)