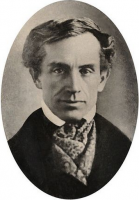

Samuel F.B. Morse, in full Samuel Finley Breese Morse (1791 — 1872), American painter and inventor who, independent of similar efforts in Europe, developed an electric telegraph (1832–35). In 1838 he developed the Morse Code.

Early Life and his Education Career

Morse was the son of Jedidiah Morse, the distinguished geographer and Congregational clergyman. From Phillips Academy in Andover, where he had been an unsteady and eccentric student, his parents sent him to Yale College (now Yale University). Although an indifferent scholar, his interest was aroused by lectures on the then little-understood subject of electricity. To the distress of his austere parents, he also enjoyed painting miniature portraits.

After graduating from Yale in 1810, Morse became a clerk for a Boston book publisher. But painting continued to be his main interest, and in 1811 his parents helped him to go to England in order to study that art. During the War of 1812, between Great Britain and the United States, Morse reacted to the English contempt for Americans by becoming passionately pro-American. Like the majority of Americans of his time, however, he accepted English artistic standards, including the “historical” style of painting—the romantic portrayal of legends and historical events with personalities gracing the foreground in grand poses and brilliant colours.

Inventing the telegraph and Morse code

Morse conceived of the idea of the single-circuit, electro-magnetic telegraph while on a ship travelling back to the United States from Europe in 1832. With some assistance from Leonard Gale, a university science professor, Morse spent the next five years developing his ideas into a working model. This included the use of a code of dots and dashes for the letters of the alphabet, which became known as the Morse Code. The dots and dashes were transmitted as short and long electrical impulses with gaps in between.

He began demonstrating the telegraph to businessmen, hoping that private investors would finance construction of a telegraph line. When no private investments came, he spent a year constructing a better model and then demonstrated this to the American government. Again no financial support. Morse spent a year in England and Europe trying to gain financial support, but still he failed.

On returning to the United States, he tried to gain the interest of the public. He laid an insulated wire across New York harbour and announced in the newspapers that he would give a public demonstration. Unfortunately, when a ship’s anchor caught his wire and it was cut, Morse received ridicule instead of support. During these 11 years of frustration, Morse was penniless and frequently hungry, but he never took his eyes off God. During this time, Morse wrote, ‘I am perfectly satisfied that, mysterious as it may seem to me, it has all been ordered in view of my Heavenly Father’s guiding hand’.

In 1843, Morse made another attempt to interest the American government in financing the telegraph. This time he succeeded. Despite a number of technical difficulties, he successfully built the first telegraph line from Washington to Baltimore within the allotted budget and within the specified time. On Friday May 24, 1844, all was in readiness. The words of the first official message were chosen by a young Christian lady, the daughter of a lifelong friend of Samuel Morse. She chose the words ‘What hath God wrought’ from the Bible (Numbers 23:23) because she recognized that it was God who had inspired and sustained Morse throughout.

Morse was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1815.

Despite honors and financial awards received from foreign countries there was no such recognition in the U.S. until he neared the end of his life, when on June 10, 1871 a bronze statue of Samuel Morse was unveiled in Central Park, New York City. An engraved portrait of Morse appeared on the reverse side of the United States two-dollar bill silver certificate series of 1896. He was depicted along with Robert Fulton. An example can be seen on the website of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco's website in their "American Currency Exhibit"

A blue plaque was erected to commemorate him at 141 Cleveland Street, London, where he lived from 1812 to 1815.

According to his The New York Times obituary published on April 3, 1872, Morse received respectively the decoration of the Atiq Nishan-i-Iftikhar (English: Order of Glory) [first medal on wearer's right depicted in photo of Morse with medals], set in diamonds, from Sultan Abdulmecid of Turkey (c.1847), a "golden snuff box containing the Prussian gold medal for scientific merit" from the King of Prussia (1851); the Great Gold Medal of Arts and Sciences from the King of Württemberg (1852); and the Great Golden Medal of Science and Arts from Emperor of Austria (1855); a cross of Chevalier in the Légion d'honneur from the Emperor of France; the Cross of a Knight of the Order of the Dannebrog from the King of Denmark (1856); the Cross of Knight Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic, from the Queen of Spain, besides being elected member of innumerable scientific and art societies in this United States and other countries. Other awards include Order of the Tower and Sword from the kingdom of Portugal (1860); and Italy conferred on him the insignia of chevalier of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus in 1864. Morse's telegraph was recognized as an IEEE Milestone in 1988.

On April 1, 2012, Google announced the release of "Gmail Tap", an April Fools' Day joke that allowed users to use Morse Code to send text from their mobile phones. Morse's great-great-grandnephew Reed Morse—a Google engineer—was instrumental in the prank, which became a real product.