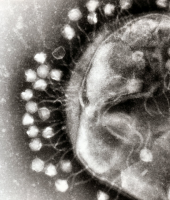

Bacteriophages or "phage" are viruses that invade bacterial cells and, in the case of lytic phages, disrupt bacterial metabolism and cause the bacterium to lyse [destruct]. Phage Therapy is the therapeutic use of lytic bacteriophages to treat pathogenic bacterial infections.

Invention History

The discovery of bacteriophages was reported by Frederick Twort in 1915 and Felix d'Herelle in 1917. D'Herelle said that the phages always appeared in the stools of Shigella dysentery patients shortly before they began to recover.He "quickly learned that bacteriophages are found wherever bacteria thrive: in sewers, in rivers that catch waste runoff from pipes, and in the stools of convalescent patients."Phage therapy was immediately recognized by many to be a key way forward for the eradication of bacterial infections. A Georgian, George Eliava, was making similar discoveries. He travelled to the Pasteur Institute in Paris where he met d'Hérelle, and in 1923 he founded the Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia, devoted to the development of phage therapy.

Bacterial Host Specificity

The bacterial host range of phage is generally narrower than that found in the antibiotics that have been selected for clinical applications. Most phage are specific for one species of bacteria and many are only able to lyse specific strains within a species. This limited host range can be advantageous, in principle, as phage therapy results in less harm to the normal body flora and ecology than commonly used antibiotics, which often disrupt the normal gastrointestinal flora and result in opportunistic secondary infections by organisms such as Clostridium difficile. The potential clinical disadvantages associated with the narrow host range of most phage strains is addressed through the development of a large collection of well-characterized phage for a broad range of pathogens, and methods to rapidly determine which of the phage strains in the collection will be effective for any given infection.

Advantages Over Antibiotics

Phage therapy can be very effective in certain conditions and has some unique advantages over antibiotics. Bacteria also develop resistance to phages, but it is incomparably easier to develop new phage than new antibiotic. A few weeks versus years are needed to obtain new phage for new strain of resistant bacteria. As bacteria evolve resistance, the relevant phages naturally evolve alongside. When super bacterium appears, the super phage already attacks it. We just need to derive it from the same environment. Phages have special advantage for localized use, because they penetrate deeper as long as the infection is present, rather than decrease rapidly in concentration below the surface like antibiotics. The phages stop reproducing once as the specific bacteria they target are destroyed. Phages do not develop secondary resistance, which is quite often in antibiotics. With the increasing incidence of antibiotic resistant bacteria and a deficit in the development of new classes of antibiotics to counteract them, there is a need to apply phages in a range of infections.

Lytic phages are similar to antibiotics in that they have remarkable antibacterial activity. However, therapeutic phages have some advantages over antibiotics, and phages have been reported to be more effective than antibiotics in treating certain infections in humans and experimentally infected animals. For example, in one study, Staphylococcus aureus phages were used to treat patients having purulent disease of the lungs and pleura. The patients were divided into two groups; the patients in group A (223 individuals) received phages, and the patients in group B (117 individuals) received antibiotics. Also, this clinical trial is one of the few studies using i.v. phage administration (48 patients in group A received phages by i.v. injection). The results were evaluated based on the following criteria: general condition of the patients, X-ray examination, reduction of purulence, and microbiological analysis of blood and sputum. No side effects were observed in any of the patients, including those who received phages intravenously. Overall, complete recovery was observed in 82% of the patients in the phage-treated group as opposed to 64% of the patients in the antibiotic-treated group. Interestingly, the percent recovery in the group receiving phages intravenously was even higher (95%) than the 82% recovery rate observed with all 223 phage-treated patients.